The Great Pyramid, situated on the Giza Plateau just west of the Nile River in Egypt, was constructed using approximately 2 500 000 limestone blocks, weighing from one and a half to ten tons each. Several granite blocks used in the construction of the largest of the interior chambers weigh up to fifty tons each. The total mass of the structure is estimated at 6 500 000 tons (Franz Löhner. www. Cheops-pyramide.ch). The pyramid is thought to have been built around 2500 B.C., making it 4500 years old. That human beings were able to design and construct a building that was capable of enduring for four and a half millennia is impressive enough. When we consider that, according to our modern historical perspective, these builders lived at the dawn of civilization, we enter the realm of mystery. How could people not long emerged from the Stone Age have achieved one of the greatest architectural wonders of human history? There is no known documentation of how, or by whom, the Great Pyramid and its companions on the Giza Plateau were built. However, the facts revealed within the structures themselves speak volumes about the people who constructed them. Several of these facts offer serious challenges to our understanding of history, particularly as it pertains to the chronology of mathematical and technological development. Upon closer examination it becomes obvious that whoever built the Pyramids employed master surveyors who were mathematically more advanced, and had a greater understanding of astronomy and of the physical nature of the Earth than is normally attributed to this epoch in human history. We will look at several of these facts in turn, and consider their implications. But first we will describe what it is that a surveyor does.

Today the job of a surveyor is much the same as it would have been forty-five centuries ago: to establish known points of reference on the Earth, and from these points make accurate measurements of the land. These measurements are made using distances and angles both on the horizontal plane and also vertically, allowing the topographical relief of the land to be ascertained and recorded. The data collected by surveyors is used to create plans and maps for such wide-ranging purposes as navigation, the establishment of public and private property lines and, pertinent to our present inquiry, the undertaking of large construction projects. Although the tools of the trade have changed, the goals are much the same as they were forty-five centuries ago. And the primary goal is now, and will be shown to have been in the days the Pyramids were built, precision.

The Greek historian, Herodotus, wrote the earliest known description of the Giza Pyramids following his visit in 440 B.C. At that time, of course, the pyramids were as old to him as he is to us. He reported that the pyramids were still covered with highly polished limestone casing stones, cut at the exact angle of the slope (51° 50′ 40″), and fitted together with almost imperceptible seams not more than half of one millimetre wide. The impression created must have resembled a seamless edifice glowing brilliantly under the Egyptian sun. These casing stones numbered from one hundred to two hundred thousand, covering an area of almost 86 000 square metres on the Great Pyramid alone. They have since mostly disappeared as a result of being shaken loose by an massive earthquake that hit Northern Egypt in the fourteenth century, and subsequently being used in rebuilding Cairo, which lies just to the Northeast.

In 1763, Nathaniel Davidson, British Consul at Algiers, visited the Giza Plateau and advanced the knowledge of the inner chambers of the Great Pyramid. He also confirmed by measurement that the sides of the pyramids face the cardinal points of the compass. (John DeSalvo, Ph.D. Great Pyramid of Giza Research Association, http://www.gizapyramid.com/index.html) This is interesting, not only because the compass made its first known appearance in China almost twenty-five centuries later (and another fourteen centuries after that in Europe), but also because it suggests that the builders had a clear concept of the Earth as a rotating sphere, with a north and a south pole, and the means to determine the directions of these poles.

It is not until the extensive survey done by W.M. Flinders Petrie in 1880-82 that the extreme precision of almost every detail of the construction became apparent. Petrie established that the Pyramids are aligned to within three arc minutes of north. When measuring angles, each degree is 1/360th of a complete circle. And each degree can be divided into sixty arc minutes, each of which can be divided into sixty arc seconds. That means that the Pyramids are oriented to within one twentieth of a single degree of North. By comparison, the Meridian Building at the Greenwich Observatory in England is oriented to within nine arc minutes of north, an error of about one sixth of a degree. The pyramid builders achieved an orientation three times more precise, 4500 years ago, and they were working with six and a half million tons of stone.

The sexagesimal, or base sixty, system of counting goes back to Babylonian times, predating even the Egyptian Dynastic Period to which the Pyramids of Giza are attributed. We know it today not only as our principle way of measuring angles and direction, but more mundanely as the way we measure time. The Babylonians were among the first to do both of these things in multiples of sixty. In light of this, it is quite remarkable that The Great Pyramid is located less than a mile south of the thirtieth parallel. That is to say, almost exactly 30° north of the Equator, as we measure it today, and more significantly, as it could theoretically have been measured forty-five hundred years ago. Considering that the actual location to the north is entirely unsuitable for the nature of construction involved in the Pyramids, the minute lack of precision in this detail need not be attributed to an error on the part of the ancient surveyors. This all may be a coincidence; however, in light of their apparent knowledge of global geography and the fact that the sexagesimal system was known to be in use at the time, it is not impossible to imagine that this site was chosen in full awareness of its global position.

When appraising the level of surveying ability involved in their construction, one needs to look no further than the actual physical details of the Pyramids as they have been measured in recent times. For the most part, the technical details used here are drawn directly from the survey carried out by Flinders Petrie in 1880-82, which were exhaustive and have since been confirmed by today’s advanced electronic equipment to be accurate within a very small range of error. The advantage of using Petrie’s data is that, since his time, parts of the structures have deteriorated enough to alter their dimensions. We will focus primarily on the Great Pyramid, as it is known, for it embodies the mystery of the Giza Plateau more than any other feature.

Consider first the lengths of this pyramid, known by the Greeks as Cheops, and by the Egyptians as Khufu. The north, east, south and west sides measure 230.363m, 230.320m, 230.365m, and 230.342m, respectively. The differences of these lengths from the average (230.348m) range from a maximum of 2.5cm to as little as 6mm. The difference between the longest and shortest sides is 4.5cm. This amounts to an error of approximately 0.002% of the average length. One must keep in mind that the construction materials involved were cut limestone blocks weighing many tons each. Next let us look at the corners of the structure. Having established that the sides are, for all intents and purposes, equal, all that remains in order to define the base of Khufu as being perfectly square is to show that the four corners are comprised of right angles. Accordingly, we see that the deviation from ninety degrees of the four corners ranges from three and a half arc minutes (or approximately one seventeenth of one degree) at the south-east corner to two arc seconds (or one 1800th of one degree) at the north-west corner. So we have 6 500 000 tons of stone covering a 5.3 hectare (13 acre) area that is almost perfectly square, and aligned to within a fraction of a degree of north. This indeed is a miracle of the surveyor’s art, in any epoch.

Next we come to one of the more interesting facts embodied in The Great Pyramid. According to conventional history, Pi, the number 3.14, is not supposed to have been calculated by any civilization until the Greeks in the third century B.C. However, the Pyramid`s original height (the top stones are missing) of 146.71m has precisely the same relationship to its base perimeter of 921.39m that the radius of a circle or sphere has to its circumference: 2Pi. (To illustrate, 146.71 x 3.14 x 2 = 921.339) It effectively functions as a model, in pyramid form, of a perfect hemisphere. It`s not hard to understand why some have proposed that it may have been designed to represent the northern hemisphere of our planet on a scale of 1:43200. (Graham Hancock, Robert Bauval, the Message of the Sphinx. William Heinemann Ltd. Great Britain, 1996) Regardless of its intended purpose, the fact that Pi is incorporated into its design strongly implies that its builders were aware of, and used this potent mathematical ratio.

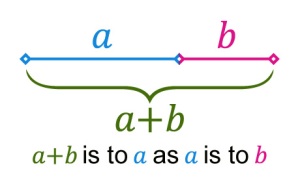

This brings us to another Greek letter, and another potent mathematical ratio: Phi, otherwise known as The Golden Ratio. Two quantities are in the Golden Ratio if the ratio between the sum of those quantities and the larger one is the same as the ratio between the larger one and the smaller one.

This ratio is ubiquitous in art, science, mathematics and even in nature. The patterns of leaves and branches, the spiral arrangement of pinecones or seeds in a sunflower, the swirls in a seashell, mathematical aspects of music, and even the spiral shape of the Milky Way Galaxy are all described in terms of the Golden ratio.

There are many ways that Phi can be shown to be incorporated into the site plan of the three Pyramids at Giza. The simplest is as follows. Measuring from apex to apex, the east-west distance from the Great Pyramid to the Third Pyramid is in a Golden Ratio to the north-south distance between the Great and Second Pyramids. Similarly, the north-south distance between the Second and Third Pyramids is in a Golden Ratio to the east-west distance between them.

When illustrated, these measurements create two Golden Rectangles. A Golden Rectangle is defined as one whose length and width are in a Golden Ratio to each other.

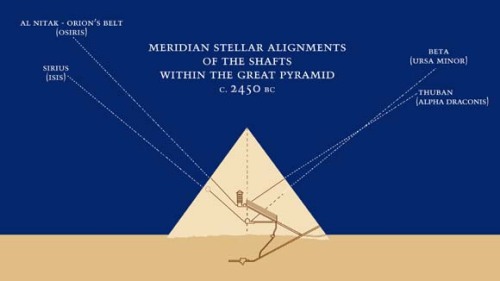

The final feature we will examine brings us to the interior of the Great Pyramid itself. Inside there are three chambers, each possessing remarkable properties which we don’t have the time or space to deal with here. From two of these chambers, called the King’s chamber and the Queen’s Chamber, extend four narrow shafts, two from each chamber. They emanate at precise angles directly toward the north and south faces of the pyramid. They have average dimensions of 22 x 23 cm. They were constructed at the same time as the pyramid, necessitating special blocks that were carved at the appropriate angle to be placed strategically as the pyramid rose in height. This in itself is an impressive feat of architectural engineering, but still more impressive is the actual alignment of the shafts. They point to the stars.

Today they have no significant relationship with any specific stellar bodies. However, thanks to modern star-mapping computer programs, we are able to simulate the sky over Giza in any given epoch, and if we turn the clock back to 2500 B.C. we see that each of these shafts target specific stars as they culminate the meridian. When a star passes each night across the imaginary line traversing the sky from north to south, it reaches its highest point above the horizon, and is said to “culminate the meridian”. The shafts, oriented due north and due south, each target a star that was significant to ancient Egyptian theology. From the Queen’s Chamber, the north shaft targets Kochab (Beta Ursa Minor, in the Little Dipper) which represented cosmic regeneration and the immortality of the soul. The south shaft targets Sirius (Alpha Canis Major, in the Great Dog constellation) which represented Isis, the cosmic mother of the kings of Egypt. From the King’s Chamber, the north shaft targets Thuban (Alpha Draconis, in the Dragon constellation) which represented cosmic pregnancy and gestation. Finally, the south shaft targets Al Nitak (Keta Orionis, in the constellation of Orion`s Belt) which represented Osiris, the high god of resurrection and rebirth, and who was the legendary bringer of civilization to the Nile Valley in a remote epoch called Zep Tepi, which translates as the First Time. (Graham Hancock, Robert Bauval, the Message of the Sphinx. William Heinemann Ltd. Great Britain, 1996) The figure below illustrates these alignments.

These alignments were quite accurate, and were valid for only approximately one hundred years, precisely during the period that the Giza Pyramids are presumed to have been built. This only hints at the staggering amount of astronomical knowledge incorporated into the monuments at Giza, of which there is ample documentation in print. But it is enough to indicate that the builders and surveyors of the Great pyramid had a deep awareness and appreciation of astronomy, and that their surveying prowess was easily up to the task of orienting the monument, not only to the cardinal points of the Earth with a level of precision beyond today’s standards, but to the heavens themselves.

The implications of the facts we have examined, and many more that we have not, are the fuel of fevered speculation and wide-ranging theories regarding the history of ancient Egyptian culture and, indeed, the evolution of civilization itself. The mystery of how and why the Pyramids of Giza were built is as old as the Pyramids themselves. None the less, these facts point to certain unavoidable conclusions as far as the people who built the monuments. The extreme precision with which they were oriented and constructed speaks of people with a level of surveying ability at least equal in accuracy and rigour to today’s standards. Their geographical positioning implies much greater geospatial awareness than has been attributed to any civilization in antiquity. The complex mathematical concepts embodied in the structures indicate a significant underestimation of the level of advancement in this field at this epoch. And the astronomical nature of the site, exemplified in The Great Pyramid, reveals an advanced relationship with the cosmos.

It is interesting to note that many prominent classical Greek thinkers studied in Egypt and visited the pyramids, including Pythagoras, who is credited with many revolutionary advances in mathematics, Erosphenes, who among others came quite close to an accurate measurement of the Earth, which was known by the Greeks to be a rotating sphere orbiting the sun, and Plato, who spent thirteen years studying in Egypt, and who believed that the Egyptians were keepers of ancient wisdom that had been handed down from a prehistoric, antediluvian civilization, and was in turn handed down to Greece.

Sources:

J.A.R. Legon, ‘The Plan of the Giza Pyramids‘, Archaeological Reports of the Archaeology Society of Staten Island, Vol.10 No.1. (New York, 1979)

W.M.F. Petrie, The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh (London, 1883).

First edition only for full details, 34-36.

J.H.Cole, The determination of the exact size and orientation of the Great Pyramid of Giza, (Survey of Egypt, paper no.39), (Cairo, 1925).

John DeSalvo, Ph.D Great Pyramid of Giza Research Association http://www.gizapyramid.com/index.html

Pyramides de Giza. http://www.biblelieux.com/giza.htm

The Global Education Project. GizaOnline http://www.theglobaleducationproject.org/index.php.

Franz Löhner. www. Cheops-pyramide.ch

Graham Hancock, Robert Bauval, the Message of the Sphinx. William Heinemann Ltd. Great Britain, 1996

That was great, Mike, and big, wide; just what I needed on a monday night. I wondered for a moment if you were going to invoke an Atlantis theory…but some essays should not be forgiving, and you were right to keep focused. Mysteries, and the unexplainable were nicely implied.

Nice perspective.

Hi,

It’s nice to see your blog, I’d like to invite you to visit my blog Tourist Cup

I wish you find something is interesting there

http://touristcup.blogspot.com/2011/02/great-giza-pyramids-amazing-facts-part.html

You are more than Welcome 🙂